By Guest Blogger Jen Seeba

This a marathon, not a sprint. But it’s been over a year, we are still running, and there is no finish line.

“I wet the bed,” my 7-year-old daughter mumbles as she crawls into bed with us. Odd — this is my girl who potty-trained in a week and never turned back. When I go to pull the sheets off the bed, my heart drops. Something is wrong. This is not a wet bed, this is a soaked bed – the pillows, the comforter – everything is drenched.

We go to the pediatrician. I tend to think worst case scenario, so it was easy to tell myself I was overreacting again. The look on the nurse’s face as the number popped up on the glucometer is ingrained in my mind; she knew I was looking and that I knew what it meant. I call my husband in tears and tell him to meet us at the Emergency Department. He has no medical background; he doesn’t know what this means yet.

The next 36 hours are a blur – a rotating door of physicians, nurses, diabetes educators, nutritionists, and social workers trying to give us the tools and reassurance we need to get through our first days at home. There is no 9 months to prepare; we are sent home with this baby less than 36 hours after that first glucometer reading.

The next 36 hours are a blur – a rotating door of physicians, nurses, diabetes educators, nutritionists, and social workers trying to give us the tools and reassurance we need to get through our first days at home. There is no 9 months to prepare; we are sent home with this baby less than 36 hours after that first glucometer reading.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease in which insulin-producing cells in the pancreas are mistakenly destroyed by the body’s immune system. Insulin is the hormone that controls blood sugar levels; it is the key your body uses to bring glucose into your cells. When cells can’t get glucose for energy, the body begins to break down fat and muscle. When this happens, ketones (fatty acids) are produced and cause a life-threatening chemical imbalance called diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). They don’t know exactly why T1D happens, but they do know that environmental triggers, such as viruses, may trigger an autoimmune response in people who are genetically predisposed to T1D. Long-term complications of diabetes include damage to your eyes, kidneys, nerves, skin, heart, and blood vessels.

Warnings signs (listed below with our personal experience in parenthesis) are often mistaken for stomach flu or virus, strep throat, urinary tract infection, or, like us, growth spurt.

Warnings signs (listed below with our personal experience in parenthesis) are often mistaken for stomach flu or virus, strep throat, urinary tract infection, or, like us, growth spurt.

- Excessive thirst (extra glass or two of water with dinner)

- Frequent urination (waking up in the middle of the night to urinate)

- Bedwetting or heavy diaper

- Vision change + headaches

- Rapid weight loss (or lack of weight gain over a period)

- Increased appetite

- Irritability + mood changes

- Fatigue + weakness

- Stomach pain, nausea + vomiting

- Fruity breath odor

- Rapid, heaving breathing

T1D is a manageable disease, but it is tedious, unpredictable, and all-encompassing. It’s really hard work to mimic the function of an internal organ. My mind is in constant motion assessing the timing, intake, and nutrition of food, the vigor of activity, the supplies we have packed, if equipment is working, and if/when/how we should adjust her insulin regimen. Just about everything can affect blood glucose concentrations – the type of carbohydrate, fat and protein content of food, exercise and its intensity, stress, lack of sleep, hormones, environmental temperature, and altitude. And that’s just off the top of my head.

T1D is a manageable disease, but it is tedious, unpredictable, and all-encompassing. It’s really hard work to mimic the function of an internal organ. My mind is in constant motion assessing the timing, intake, and nutrition of food, the vigor of activity, the supplies we have packed, if equipment is working, and if/when/how we should adjust her insulin regimen. Just about everything can affect blood glucose concentrations – the type of carbohydrate, fat and protein content of food, exercise and its intensity, stress, lack of sleep, hormones, environmental temperature, and altitude. And that’s just off the top of my head.

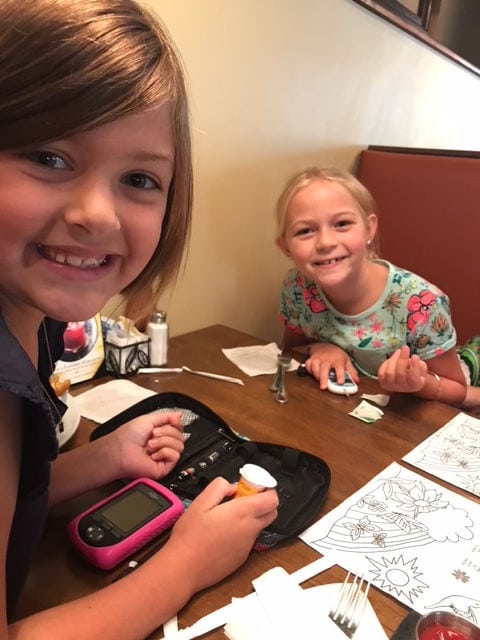

Everything has extra layers of worry now. Throwing up can easily be a medical emergency. Untreated hypoglycemia can lead seizures, coma, and death. We take the day off to go on all the school field trips. We hover at sporting events and practices. We wake up in the middle of the night every night to check blood sugar. We react to the alarms on her continuous glucose meter (CGM) and text her teacher, drag ourselves out of bed to check her, step outside to pull her away from playing with her friends one more time.

But, I am not the one living with it. The devices she wears are noticeable on her tiny frame and often prompt questioning glances that she doesn’t always know how to address. I have spent hours consoling a young girl who can’t think clearly because she is hyperglycemic or irritable because she is hypoglycemic, a girl who has catheters inserted and needles poked and food shoved into her sleepy body, a girl who has to sit out to recover for reasons no one can see and who has to wait to eat until her carbs are counted or has to eat even when she doesn’t feel like it, a girl who can’t go to the sleepover because I can’t place that responsibility or trust in someone else. She did nothing to deserve this, but she is handling it with such grace and unwavering strength. She is so brave and smart and we are so very proud of her. And we are proud of my 5-year-old son, who does not have diabetes, because this disease affects him too – how he eats, how he plays, and most obviously, how attention is often diverted away from him.

T1D is an invisible disease, but it is chronic and constant; you don’t get a day off. And, to date, there is no cure. JDRF has not only been a great support system to us, they educate, advocate, and raise money for much-needed research. It’s overwhelming to go to events like the JDRF Hope Gala and OneWalk and be among the brave T1D warriors as they feel the love of the community.

T1D is an invisible disease, but it is chronic and constant; you don’t get a day off. And, to date, there is no cure. JDRF has not only been a great support system to us, they educate, advocate, and raise money for much-needed research. It’s overwhelming to go to events like the JDRF Hope Gala and OneWalk and be among the brave T1D warriors as they feel the love of the community.

Don’t get me wrong, I know it could be worse. But I want it to be better. I never thought this would be our life, but it is, so we carry on as it becomes our new norm because we have no other choice. It’s hard to look at the silver lining – motivation for a healthier lifestyle, new friendships, learned responsibility – and ignore all the bad. So, we make a conscious effort to approach each day with gratitude for what we have, motivation to make things better, and compassion for all those fighting their own battle.

I had no idea that I had type II diabetes. I was diagnosed at age 50, after complaining to my doctor about being very tired. There is no family history of this disease. I’m a male and at the time of diagnosis, I weighed about 215. (I’m 6’2″)Within 6 months, I had gained 30 to 35 pounds, and apparently the diabetes medicines (Actos and Glimiperide) are known to cause weight gain. I wish my doctor had mentioned that, so I could have monitored my weight more closely. I was also taking metformin 1000 mg twice daily December 2017 our family doctor started me on Green House Herbal Clinic Diabetes Disease Herbal mixture, 5 weeks into treatment I improved dramatically. At the end of the full treatment course, the disease is totally under control. No case blurred vision, frequent urination, or weakness

Visit Green House Herbal Clinic official website I am strong again and able to go about daily activities. This is a breakthrough for all diabetes sufferers

Thanks for sharing your experience. Adult stemcells are going to help children with similar autoimmune problems. Much distance has already been covered though much more has to be done. After working with stemcells at all ages my hunch is that this generation is more fortunate than ours. Times are changing for the better. God bless the young.

Such a wonderful family! Thanks for sharing your story! Proud of beautiful, strong and brave Olive!

Thank you so much for sharing your story and creating awareness!

You are an amazing family – so proud of you all.

Thank you for sharing this story! We have friends who went through a similar situation, and it was so scary. Being able to recognize the symptoms is so important, as well as having a supportive home. You all sound like wonderful parents. Your daughter is lucky to have you by her side, and she seems like an amazing little girl!