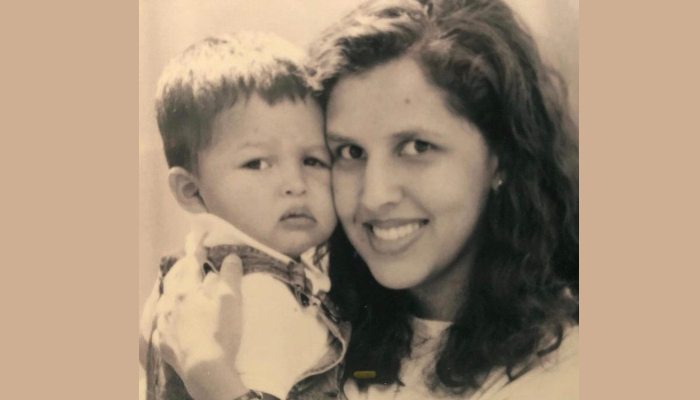

By Guest Blogger Hayluri (Luly) Beckles

This May will be 15 years since I became a member of a very special club…the kind of club no parent should ever have to join… that is the bereaved parent club.

I am fully aware that not everyone grieves the same. However, if you lost a child last week, or 10 years ago, or 40 years ago, there is a common connection that cannot be denied. And that is the tremendous pain we carry and the cherished moments we lost – no matter how much time has passed.

While we have that common connection, we also have our own unique stories and circumstances surrounding our losses. I am one of those bereaved parents who chose to speak about the loss of my son, Joshua, early on. I shared my story in a post on TMoM that you can find here. I knew many people cared for my family and me. They just did not understand, nor did I want them to understand such pain.

Prior to modern medicine, child loss was a common occurrence. When newly bereaved parents lost a child, it was likely someone else from their family or community had also experienced the unimaginable pain of losing a child and were able to provide them with support.

Today, child loss is less common. It is like the big elephant in the room. It happens, and when it does, often times those outside the grieving family do not know what to say or what to do.

When I was growing up in Venezuela, my Aunt Liz and Uncle Frank had lost their two oldest children: a set of twins (a boy and a girl.) Candelaria, died a couple of days after birth, and Franklin died of meningitis when he was just three years old. My aunt and uncle went on to have three more sons. Nonetheless, my family always talks about the twins. It is not a taboo subject. My cousins mattered. They existed. They were loved and never forgotten.

You see, child loss interrupts the cycle of life. Children are not supposed to die; they are supposed to bury their parents. Parents are not supposed to bury their own children.

Bereaved parents can sometimes feel abandoned by their family and friends. I became “scary” to approach for many people who knew me and my son Joshua. If I ran into people, they would sometimes avoid me or pretend they did not see me. I realized that I reminded them of the uncomfortable reality that children do die. I often had to comfort them instead of being the one comforted.

Recognizing how it can be difficult to comfort a grieving person, I found a list (posted below) of suggested Dos and Don’ts for bereaved parents that I shared with other over the years. Many of my friends and colleagues have found this list a great source of information. If someone close to you has experienced the loss of a child, and you do not know what to say or do, you may find the following list of resources helpful.

Suggested Dos

Do let your genuine concern and caring show.

Do be available…to listen, to run errands, to help with the other children, or whatever else seems needed.

Do say you are sorry about what has happened to their child and about their pain.

Do allow them to express as much grief as they are feeling at the moment and are willing to share.

Do encourage them to be patient with themselves, not to expect too much of themselves and not to impose any shoulds on themselves.

Do allow them to talk about the child they have lost as much and as often as they want to.

Do talk about the special endearing qualities of the child they have lost.

Do give special attention to the child’s brothers and sisters at the funeral home, during the funeral and in the months to come (they too are hurting and are confused and are in need of attention which their parents may not be able to give at this time).

Do reassure them that they did everything they could, that the medical care received was the best or whatever else you know to be true and positive about the care given their child.

Suggested Don’ts

Don’t let your own sense of helplessness keep you from reaching out to a bereaved parent.

Don’t avoid them because you are uncomfortable (being avoided by friends adds pain to an already intolerably painful experience).

Don’t say you know how they feel (unless you have lost a child yourself, you probably do not know how they feel).

Don’t say “You ought to be feeling better by now” or anything else which implies a judgment about their feelings.

Don’t tell them what they should feel or do.

Don’t change the subject when they mention their dead child.

Don’t avoid mentioning the child’s name out of fear of reminding them of their pain (they haven’t forgotten!).

Don’t try to find something positive about the child’s death (moral lessons, closer family ties, etc.).

Don’t point out that at least they have their other children (children are not interchangeable — they cannot replace the child who is gone).

Don’t say “You can always have another child.” Even if they wanted to and could, another child would not replace the child they have lost.

Don’t suggest that they should be grateful for their other children (grief over the loss of one child, does not discount a parent’s love and appreciation of their living children).

Don’t make comments which in any way suggest that the care given their child at home, in the emergency room hospital or wherever was inadequate (parents are plagued by feelings of doubt and guilt without any help from their family and friends.).

Some people find the strength to put aside their fears and pain in order to help and support their friend or loved one. I will forever be grateful to my family, my close friends, and even some people who I did not even know, yet they provided meals for my family, picked up my sons from preschool, and stepped out of their comfort zone to be there – to be extraordinary – when it mattered the most.

* Dos and Don’ts prepared by Lee Schmidt, Parent Bereavement Outreach, Santa Monica, CA 90402 ©19

* Source for image at top: Ariel Perez

Thank you so much for helping us to love and support grieving people through your courage and clarity. I am so sorry for the loss of your son Joshua.

Thanks for your kind words Susie

Thank you for sharing your heartfelt emotions and experience. Sending love to you and other parents facing this uncomfortable reality.

Beautifully written Luly.