Why We Should Let Boys Cry

By Guest Bloggers Taylor Gabbey, Adrienne Loffredo, Liz Mechan, and Macy Nesom

“You’re being a little girl. Do we need to get you a little pink dress? Be a big boy. Quit crying!” a dad yelled at his son.

I was standing in line at the grocery store as I watched the meltdown unfold. The child was bawling after he had slipped and fallen on the floor. It took quite a bit of self-restraint to not say anything. Why couldn’t this boy cry? He was obviously hurt and possibly embarrassed from the fall. He was being told by his dad at a very fundamental age that crying – even when in pain- is bad. What emotion does that leave for young boys to feel and show?

Anger is often a secondary emotion when sadness is suppressed.

What may sound like a harmless comment can hold lifelong consequences, especially where children’s emotional development is concerned. Children learn very young which emotional expressions will be reprimanded versus which ones will be treated with more respect. For example, the phrase “Boys don’t cry,” carries several messages of invalidation. By saying don’t cry, the most natural human response to sadness is maligned, pushed aside as something inappropriate and undesirable. Even more harmful is the addition of boys; by framing the “don’t cry” message within the context of gender, this simple phrase invalidates a vital part of the child’s identity, essentially telling them that crying—and, by extension, sadness—removes their status as a male. A four-year-old who hears “real boys don’t cry” might truly believe that crying makes him literally less of a boy, and so he will begin emotionally suppressing his sadness out of fear of losing that identity. Older children, on the other hand, will instead hear the phrase as the insult it is often meant to be, and therefore respond to the statement as an overt act of discipline, discouraging the crying behavior and suppressing emotion even further.

The act of crying contrasts sharply from how parents often respond to anger in young boys. Instead of being met with “boys don’t get angry,” a child’s expression of anger is often taken more seriously. Parents are more likely to ask what triggered the anger, validate that feeling with quiet questions, and provide alternative ways to express the emotion. In some cases, a male child’s anger is even treated positively. Take, for example, the viral videos of young toddlers engaging in aggressive acts of anger, like swearing or throwing things. Even if it is well-intentioned, laughing at a child’s angry outbursts conveys to them that anger is okay and even desirable, while crying is not. The result of this emotion policing is that boys are trained to respond to all negative emotions with anger, which can create significant relationship problems later in life.

Learned behaviors in childhood will follow to adulthood.

Emotional suppression is linked to higher suicide rates beginning as early as age 16.

Boys who learn to suppress their emotions can become stoic men. Research has found that male stoicism (or openness to feelings) can be linked to relational problems. This trait of stoicism correlates to lower psychological well-being. Even worse, stoicism affects a person’s attitude towards seeking mental health care. This essentially means that a child with suppressed emotions of sadness is much more likely to have psychological issues in adulthood (such as depression) and will have a harder time asking for help because they perceive asking for help as a negative, and potentially more feminine quality.

“Problems we think of as typically male (e.g. difficulty with intimacy, workaholism, alcoholism, abusive behavior, rage) may be attempts to escape depression. Unfortunately, their attempts to escape this pain may hurt the people they love the most, and they often pass their conditions on to their children.” – Erford & Hays, 2018

What can we do?

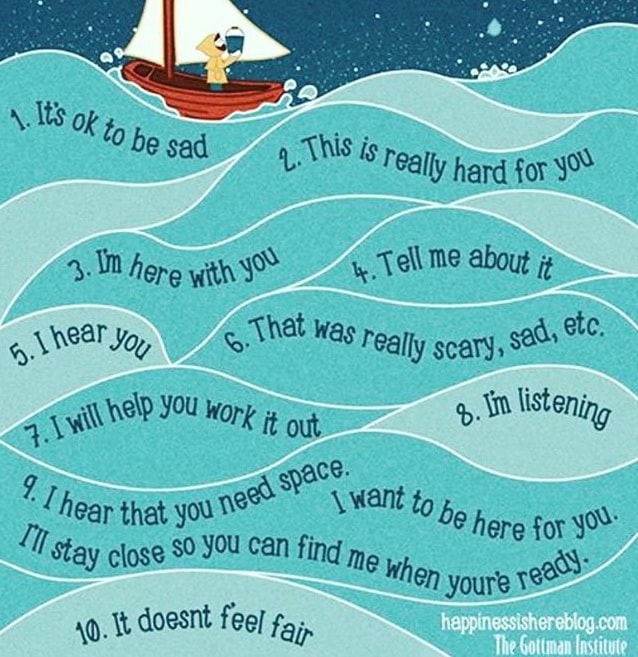

As a society, we are creating a cycle of suppression of emotions in boys. This, in turn, effects their relationships with significant others and their own children, creating cycle after cycle of severe mental health issues. Where do we start? We start with our own children. Validating emotions goes a long way. Below we have included a wonderful image from the Gottman Institute of things to stay instead of, “Stop crying.”

Kids feel the same emotions whether they are boys or girls. The difference is, how we as parents and society expect them to talk about and show their emotions or feelings.

We can normalize feeling talk. For example, instead of just asking, “How was your day?” maybe also ask, “How are you feeling today?” This allows room for children to name their emotions and work through them in a healthy way.

Here are some tips for parents of boys to keep in mind:

- Sensitivity indicates a high EQ (Emotional Intelligence).

- Boys and girls both experience sadness and hurt.

- Boys need help processing emotions – talking about how they feel – just like many girls do.

- Crying is a natural, physical response to sadness.

- Emotional suppression is linked to higher suicide rates beginning as early as age 16.

Knowing these facts, here are some things to try:

- Talk to your son(s) about their feelings.

- Read books about emotions and help boys learn to name their feelings.

- Be ready to listen when your son wants to talk about how he feels.

- Try to limit advise-giving.

- Develop regular family rituals that involve talking about feelings, such at dinner time or bed time. When asking how someone’s day was, include questions about how they felt throughout the day.

Need some easy to read resources?

Want to see more blogs like this and get notifications on local events and happenings? Subscribe to our free weekly newsletters here.

Such an important topic! Thank you for sharing this.